In Beijing

This is a small subset of nearly 900 photos we made - a number that hints at the excesses that digital cameras encourage.

Ours was a private tour, meaning that we always had a guide, driver, and car to ourselves. We flew from city to city, and as we arrived at each airport a new guide would appear and take us to our hotel. The guide would stay with us, take us to the sights and explain them, lead us to good restaurants and order the food (making sure it contained no pork or shellfish), and at the end of that city's stay take us to the airport and see us onto the next airplane.

This level of pampering may seem extreme, but was welcome in a country where we did not understand the language and could not read the script.

All of our guides were young people who had been to university and had passed a rigorous qualifying exam to become registered guides. But they do not make much money and at least one said she was going to get her master's degree and change professions. When asked, all but one said they lived out on the periphery of the city (the low-rent district) and needed about an hour via metro and/or bus to reach the center where we were quartered.

The tour was set up by Jia Thompson of Jia's Dream Tours. She listened to our requests, advised us on what we might enjoy, and tailored the itinerary to our interests and capabilities. She made all the arrangements and called us several times while we were in China to make sure everything was going well. The really surprising thing is that this private tour was not much more expensive than the usual inflexible group tour. We could not have been more pleased. (At present, Jia is no longer arranging tours and is pursuing a career as a dancer.)

In Beijing we stayed at the Bamboo Garden Hotel. 100 years ago it

was the home of a rich man. It is far and away the classiest place

we stayed in China. The coffee was superlative. (Unlike every

other cup of coffee we encountered in the hotels where we stayed.

However, we did find good coffee in some small coffee shops.)

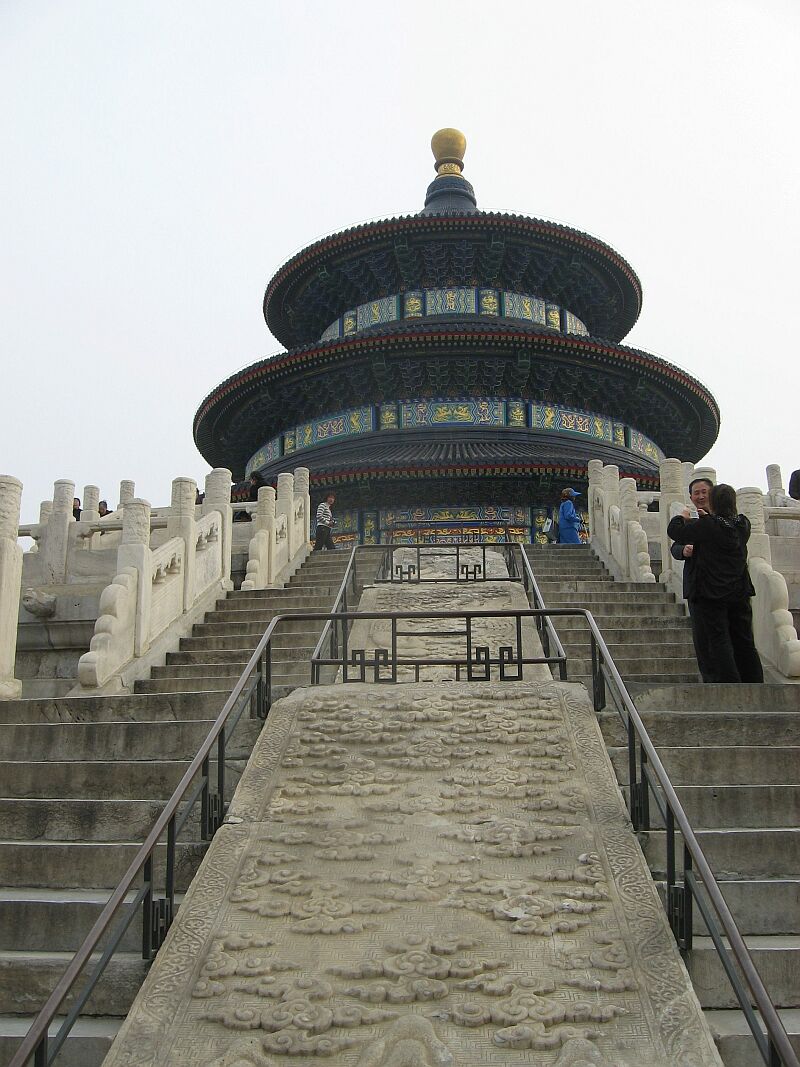

The Temple of Heaven is a Taoist complex in Southeastern Beijing.

This magnificent round building sits at the center of a large

square.

One walks through this park on the way to the Temple of Heaven.

The park was full of middle-aged and older couples and singles

dancing to swing music, people playing cards (they weren't gambling,

of course - that would be illegal!), karaoke singers, musicians

jamming on ancient instruments, etc.

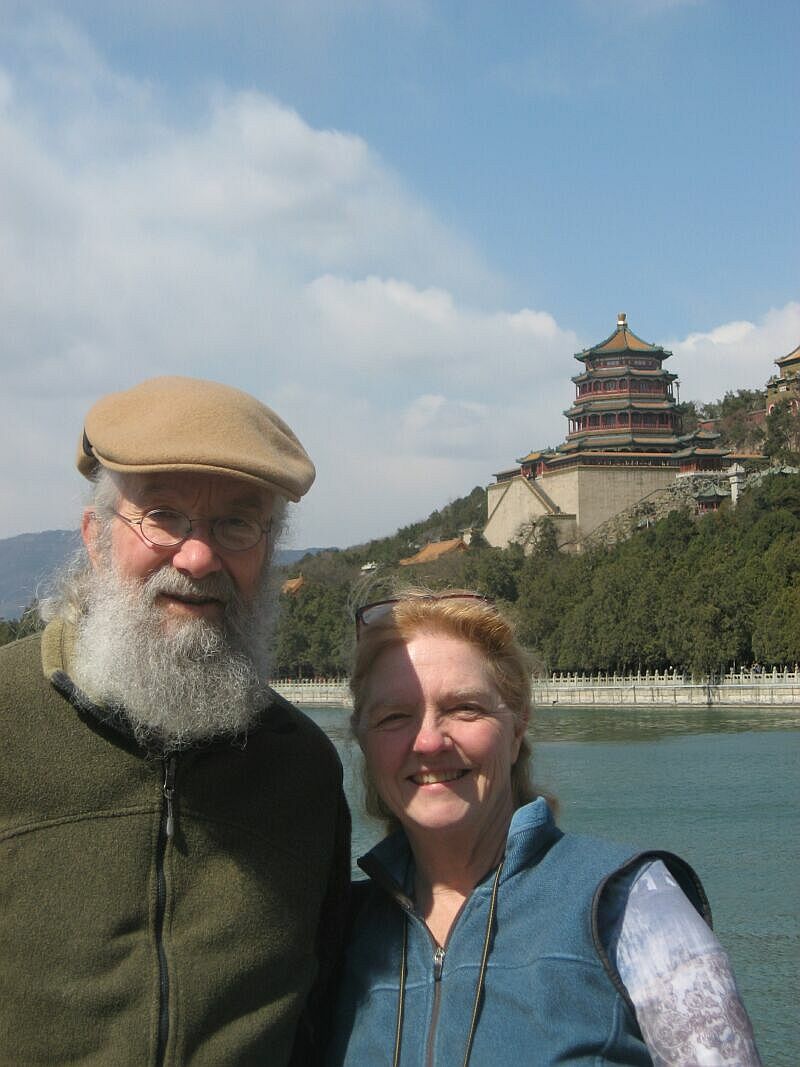

The summer palace (which is in North Beijing between the 4th and 5th

ring roads) is where the emperor and his court stayed during the warm

season. It contains a large man-made lake. A commoner and his girlfriend

were enjoying it on this day.

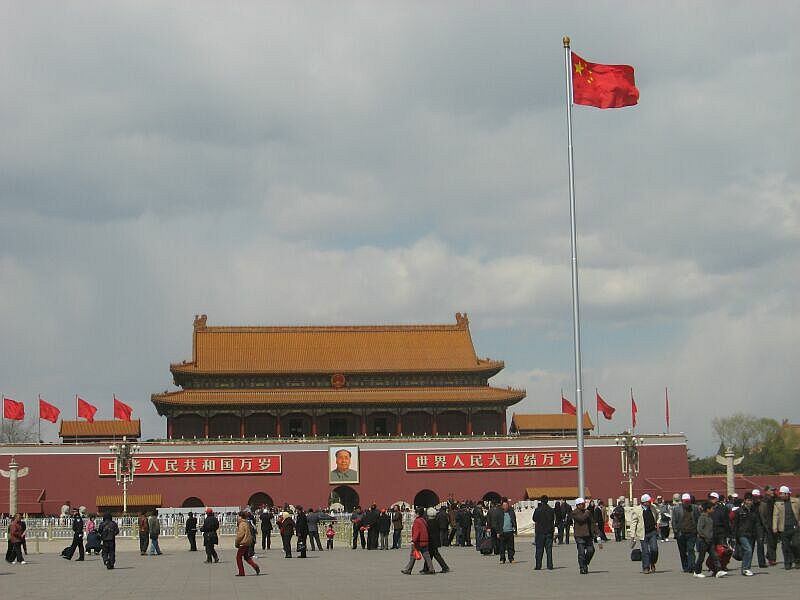

Tiananmen Square is much bigger than this picture shows. Government

buildings surround it, including the Great Helmsman's tomb and the

building where the Central Committee and other arms of government

meet to conduct the people's business. The influence of Albert Speer

seems strong here. Tiananmen Square is where the government leadership

played it safe and crushed the incipient revolution on 4 June 1989.

The photo above shows the entrance to the Forbidden City, which is

on the North side of the square.

This lion guards the Forbidden City. His right paw rests on a globe

symbolizing the planet. He is a male lion and his control of the globe

symbolizes male power. On the other side of the gate is a simlar beast,

but she is a female and so holds a cub in her paw. The symbolism is

obvious.

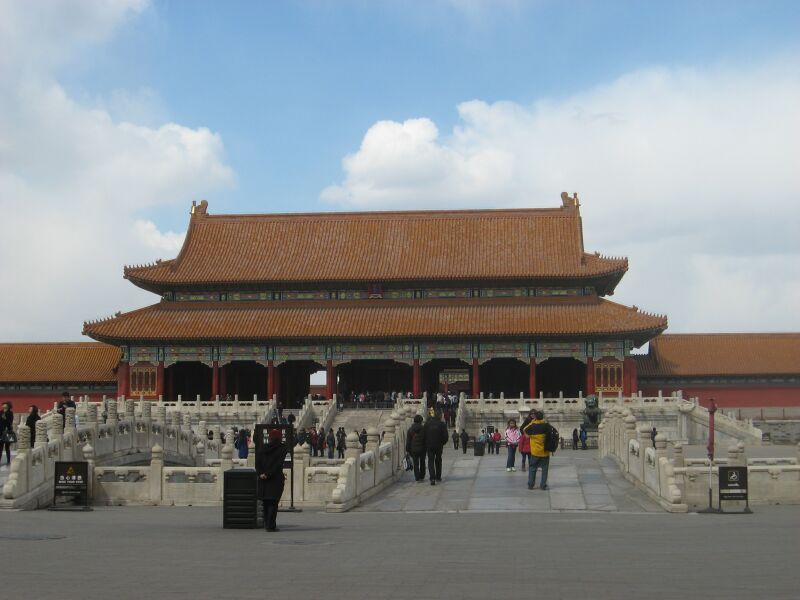

This is one of the palaces inside the Forbidden City. The Forbidden City is a 15th century complex that housed the imperial court through the end of the Qing Dynasty. It is located in the middle of Beijing and is now a museum. Note the seven little dragon figures on each upturned eave. Seven is a powerful and lucky number. The seven figures indicate that a king was resident. A prince got five, according to our guide. Five is an OK number, but it isn't seven.

If we are not mistaken this particular building (or another very

much like it - there are several in the Forbidden City) was the site

of a production of Puccini's Turandot by Zubin Mehta and some Italian

singers in 1998.

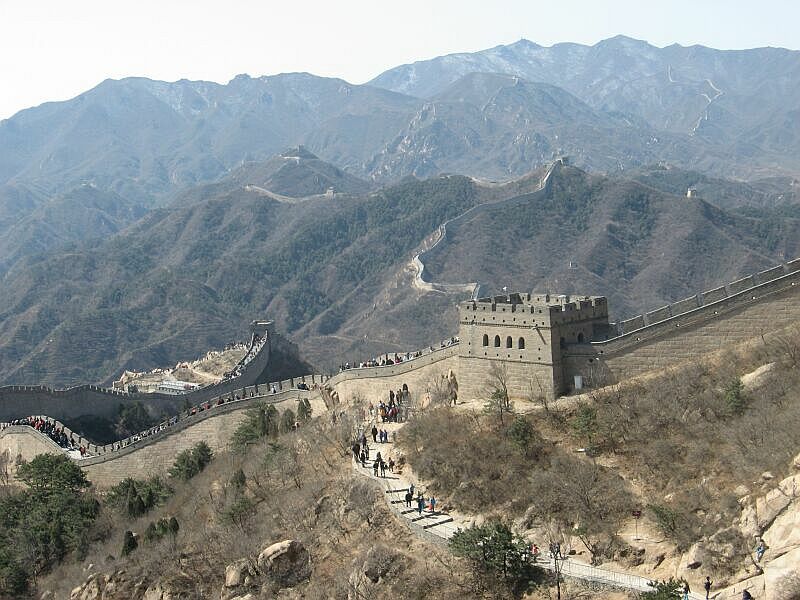

The Great Wall is about an hour's drive outside town. The Wall, like

many tourist attractions in China, swarms with visitors - 99% of them

Chinese. The Chinese are now wealthy enough to become tourists in their

own country, though not so many go as far as the US or Europe.

We watched two stories from Peking Opera in a Beijing tea house. The one shown here is called "The king's concubine must die". The king is the one with the long black beard. We found the music and the action strangely appealing - despite our unfamiliarity with the technique, and despite the fact that we remained mostly in the dark about the story as it went forward. Peking opera is within a tradition both sophisticated and (to the Westerner) alien. It is a genre that we both would like to get to know better.

Note the phoenix and dragon on the curtain behind the king. We saw this

motif repeatedly in China. The mystical qualities of these animals are

complex, but basically the dragon is yang and the phoenix is yin. You

can read about them

here and

here.

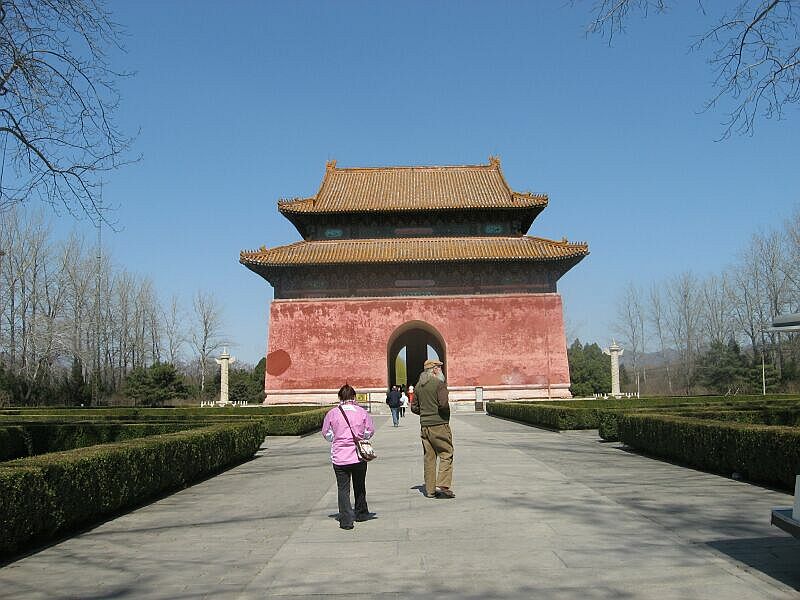

A long, very pleasant walkway is part of a complex that contains 13 Ming Dynasty tombs, North of Beijing. The structure shown above is an ornamental gate near the beginning of the walkway.

It was a cold, beautiful day. The air was the clearest we saw in China.

Our guide Maggie was always easy to find in a crowd because of her pink

coat. Her real name is not Maggie, but Chinese guides have found it

necessary to choose aliases that foreigners can pronounce.

Maggie took us to the home of a middle-class woman in a hutong not far from our hotel. This woman (she is on the left; Maggie is on the right) is unmarried and retired. Her government pension provides a decent living. She and her niece augment income by painting lovely pictures inside glass bottles. (We bought one.)

A hutong is an old-fashioned street/neighborhood of one and two story

buildings where people live and work. Most of the hutongs in Beijing

have been torn down and replaced with high-rise apartment buildings.

Most folks in Beijing live in apartment buildings. With a population of

around 15 million, there is nowhere else to put them. This is true in

most Chinese cities, where a population of one million is thought of

as small.

People are burning incense and praying at Lama Temple, a Tibetan

temple and monastery in Beijing. We visited a number of Buddhist

temples in different parts of China and found people praying in all

of them. It is clear that Buddhist religion, including the Tibetan

strain, is alive and well in China. (Falun Gong, a new religion that

emerged in the 1990's, has not been as fortunate.)

Leaving Beijing we flew several hundred miles south to Xi'an (population about 10 million). Xi'an was a terminus of the Silk Road and one of the ancient capitols of China.

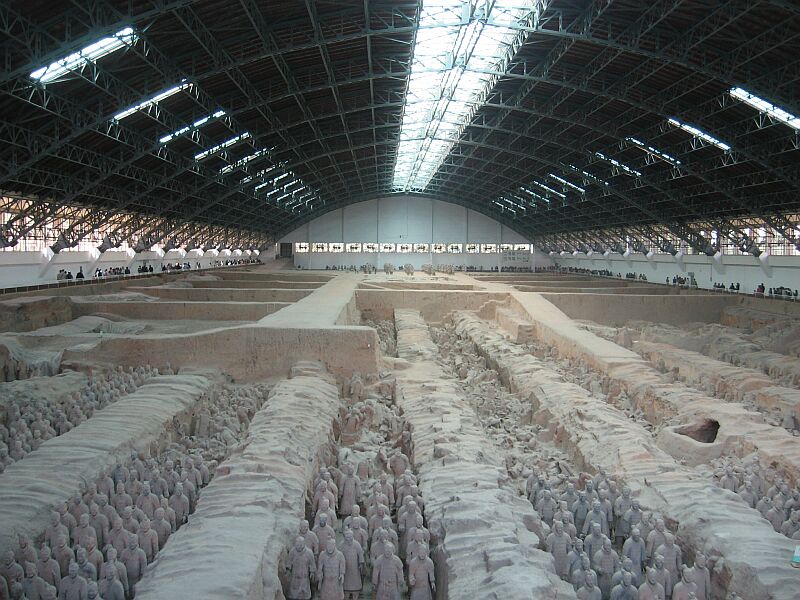

Everyone knows the story of the terracotta warriors: Some 200 years BCE the king in Xi'an tried to take it all with him when he died, including his army. This is an old story, the most familiar version of which involves the pharoahs of ancient Egypt, who also wanted to have their stuff available in the afterlife.

Most people who go to Xi'an do so to see the terracotta warriors, but

the town also has an excellent museum (Shanxi Provincial Museum)

and - even better - an excavated neolithic community (Banpo Museum)

housed under a single large roof.

In addition to the infantry in the first photo, the terracotta army

contains horsemen like this one, and war chariots. All of these figures

originally were painted in lifelike colors, which faded very quickly

when exposed to light.

Xi'an's ancient city wall is intact, in excellent condition, and

surrounds the old city on all four sides. We find this exceptional

because in Europe few city walls survived the introduction of cannon,

and like many other ancient constructions were canibalized for their

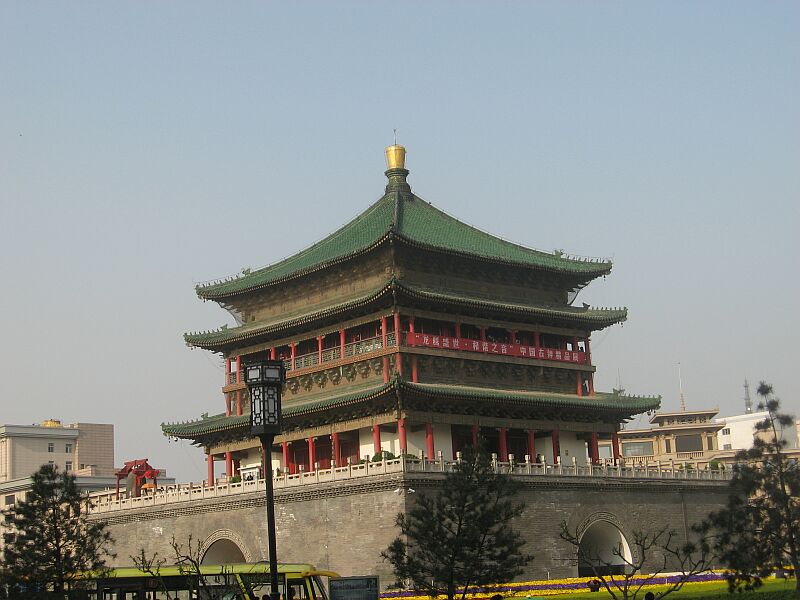

stone. Xi'an's geography also includes a perfectly preserved bell tower

at the city center and a drum tower about a block away from it. This

photo of the modern city and the moat that lies along the wall was

taken from the city wall. (Sorry, we do not have a photo of the wall

itself.) This prospect, showing a well-maintained park and residential

high-rises, is typical of Chinese cities.

Xi'an's bell tower sits at the geographic center of the city, as

defined by the city walls. The bell inside, which was used to ring

the hours, is huge. A smaller bell can be seen at the corner of the

building in the photo above. You can ring the smaller bell for a few

yuan by swinging a log at it. Our hotel was across the street.

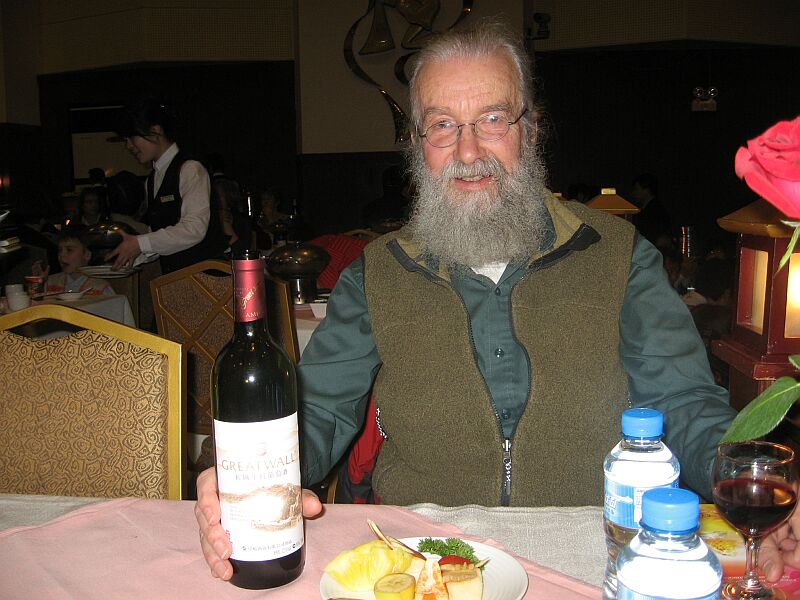

Every evening this group puts on a sort of musical revue (the Tang dynasty show) in Xi'an for western tourists, who are sitting at tables and eating dinner. It was a pleasant evening for us. It was here that we got our first (and last) taste of Great Wall wine. Stories from other travellers, plus our own limited experience, tell us that Chinese winemakers have a long way to go. (You can see that the guy in the photo below has already had a couple of glasses.)

Leaving Xi'an, we flew to Chengdu in Southwestern China. Chengdu is the capital of Sichuan; we went there mainly to get a look at Pandas in the nearby preserve and to climb the sacred mountain Emei Shan. (Chengdu is also a two-hour flight from Lhasa, where we chose not to go.)

As everyone knows, Pandas dine almost exclusively on bamboo. And they

spend a lot of their time eating. From Wikipedia:

The Giant Panda still has the digestive system of a carnivore and

does not have the ability to digest cellulose efficiently, and thus

derives little energy and little protein from consumption of bamboo.

The average Giant Panda eats as much as 9 to 14 kg (20 to 30 pounds)

of bamboo shoots a day. Because the Giant Panda consumes a diet

low in nutrition, it is important for it to keep its digestive tract

full. The limited energy input imposed on it by its diet has affected

the panda's behavior. The Giant Panda tends to limit its social

interactions and avoids steeply sloping terrain in order to limit its

energy expenditures. This animal, cute as it is, does seem like

a loser in the survival-of-the-fittest sweepstakes. It clearly is one

of Nature's dead ends.

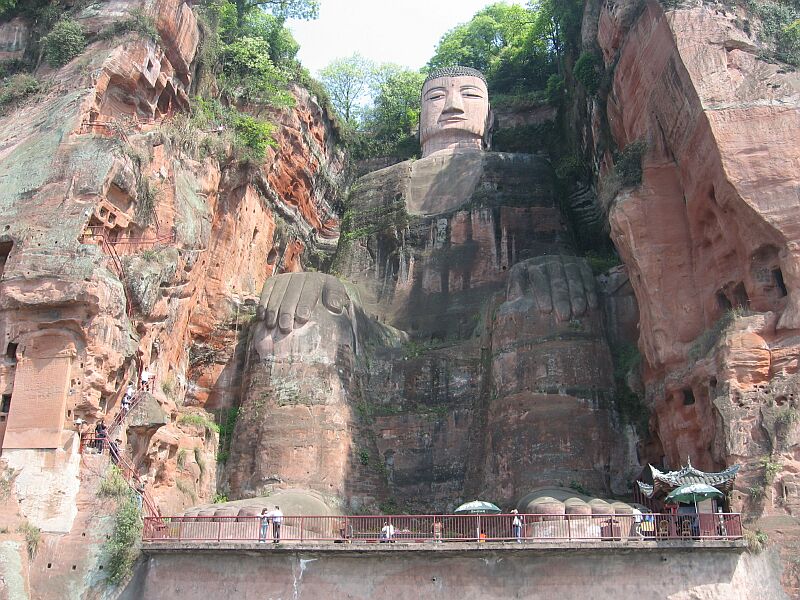

Leaving the Pandas, we drove South a couple of hours to Leshan, to

visit the nearby Big Buddha, which is carved into a mountainside and

serenely looks out across a wide river. This statue is 1200 years old

and is the largest Buddha in the world - larger, for example, than

those the shameful Taliban destroyed in Afghanistan. Note the trail

up the cliff.

We then drove on to the town of Emei, which sits at the base of Emei Shan. Emei Shan (or Mount Emei) is one of the four sacred Buddhist mountains of China. It rises to over 10,000 feet. From Emei town, a pilgrim can walk several miles to the top on trails that go past a number of temples and monasteries. But we are old and chose to drive most of the way, then walk about a mile up stone steps, and finally take a cable car to the top.

Our goal was to see the immense golden statue of the Buddha that sits at the top of Emei Shan. But the weather was cold and foggy. Standing at the base of the statue and looking upward, we could see only a few feet into the fog. The photo above was scrounged from another website. The Golden Buddha is bigger than it looks in this photo; for example, its base is actually a rather large temple. We did take the photo below, which looks into the door of that temple.

In spite of the fog the climb was not a total loss. We were there on the first day of Pesach, so after burning incense and dedicating it to the Buddha we went to a quiet spot behind the temple and did a mini-seder. This year, the start of Pesach coincided with the the Birchat HaChamah, which happens every 28 years and occurs on Erev Pesach very rarely. Birchat HaChamah is a prayer that marks the return of the sun to the place it occupied in the sky when it was created, according to the midrash. Unfortunately, we could not see the sun.

Like Leshan's Big Buddha, Emei Shan is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

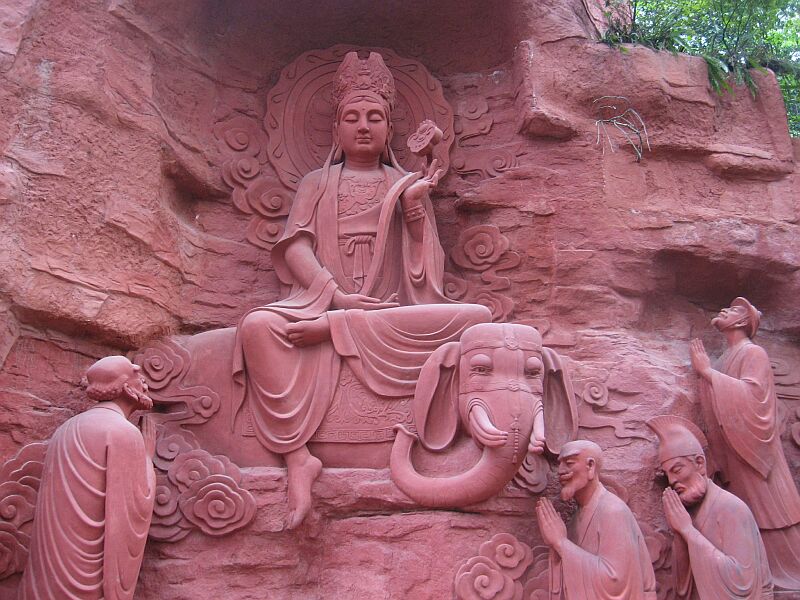

One of Emei town's many beauties is a hillside sculpted to show scenes in

Buddhist history. Above you can see Pushan, a boddhisattva who learned

directly from Shakyamuni. Note the six-tusked elephant.

Back in Chengdu we went to a performance of something called "Sichuan

Opera", though it really is more of a revue show. Every part was exciting,

and none more so than the face-changer's act. Above you see the face-changer

starting with a violet outfit and a purple face. He obscures himself

for no more than a second with the flag in his right hand, and then he

has a green face and a green outfit! You could hear jaws hitting the

floor.

From Chengdu we flew to Guilin, another "small" city whose population is probably somewhere upward of a million. Our chief interest in Guilin was its unusual karst landscape, which is shown in the photo above. The photo was taken during a leisurely three hour cruise up Li River from Guilin to a tourist trap called Yangshuo.

From an article on the web: The specific conditions for forming the

magnificent topography of Guilin are fourfold. First, you need hard,

compact carbonate rock. In Guilin, it's Devonian limestone. Secondly,

you need strong uplift, in this case provided by the collision of India

with Asia to form the Himalayas. Third, you need a monsoon climate of

high moisture during the warmest season. Finally, the area must not

have been scoured by glaciers, which this region wasn't.

Boats on Li River tend to be minimal.

Our guide in Yangshuo found it hard to believe that in America some of us regard McDonald's with contempt. Here, at least, it is one of the classiest eateries in town. The Yangshuo McDonald's differs in no significant way from a normal American McDonald's - a testament to Ray Krock's famous insistance on uniformity.

Though Yangshuo exists almost solely for tourists (the great majority of

whom are Chinese, by the way) its setting is lovely. Guilin and Yangshuo

are in South China where the ethnic composition shades into the hill

peoples of Laos, Burma, and Thailand. The night we were in Yangshuo we

went to a kind of pageant involving a light-show with ethnic singing and

dance on a lake. It was quite beautiful but our photos were disappointing.

After Guilin, our next stop was Hangzhou, which is near China's East coast South of Shanghai. Hangzhou, which has a population of about 8 million, is certainly the cleanest and most beautiful large city we have ever been in. Much of the town is parkland, and our hotel sat across the street from lovely West Lake. We have included here two photos taken in the park that surrounds West Lake.

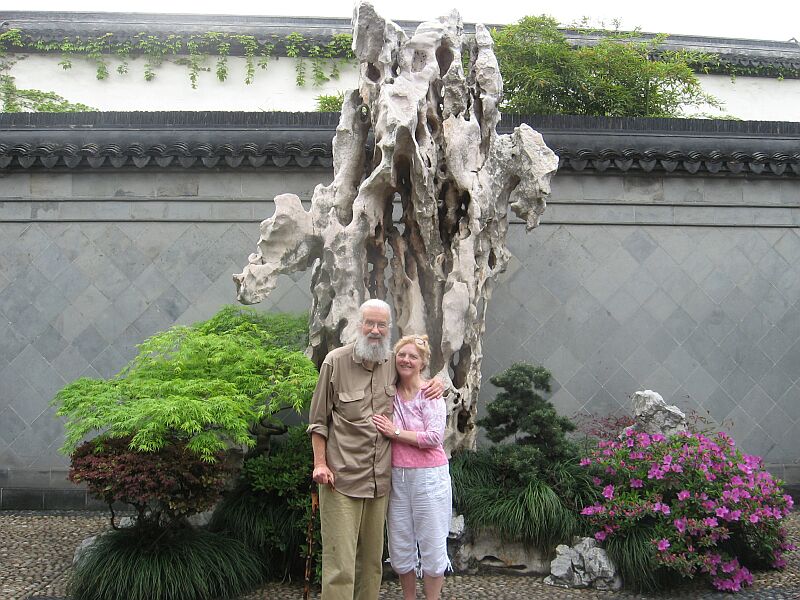

We are standing in front of a status rock, in what used to be a rich

man's house. Chinese of that era particularly liked these water-eroded

rocks (our guide told us) and wanted to have a really big one in their

garden. It was hard to move them from the mountains - they are

heavy - and only a rich man could afford the labor. Hence big rock =

high status.

Leaving Hangzhou by train, our last stop was Shanghai. Shanghai is

China's Manhattan, in terms of its clout as a financial center, and its

skyscrapers. The old-fashioned street above probably will soon be razed

for construction of high-rises.

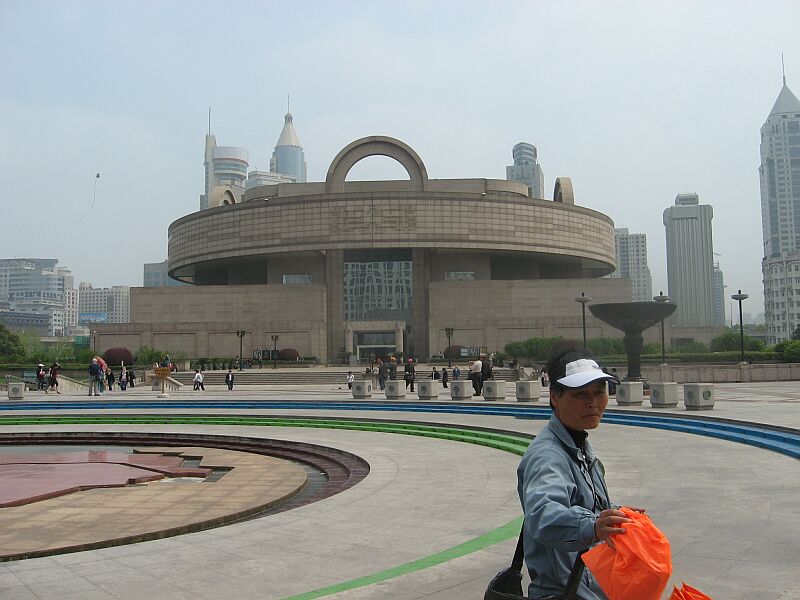

This is the Shanghai Museum, which has four floors of marvellous

collections encompassing calligraphy, painting, ceramics, coinage,

bronze, sculpture, etc. The building is both beautiful and functional

and the collections are exquisite. The man in the foreground is selling

kites.

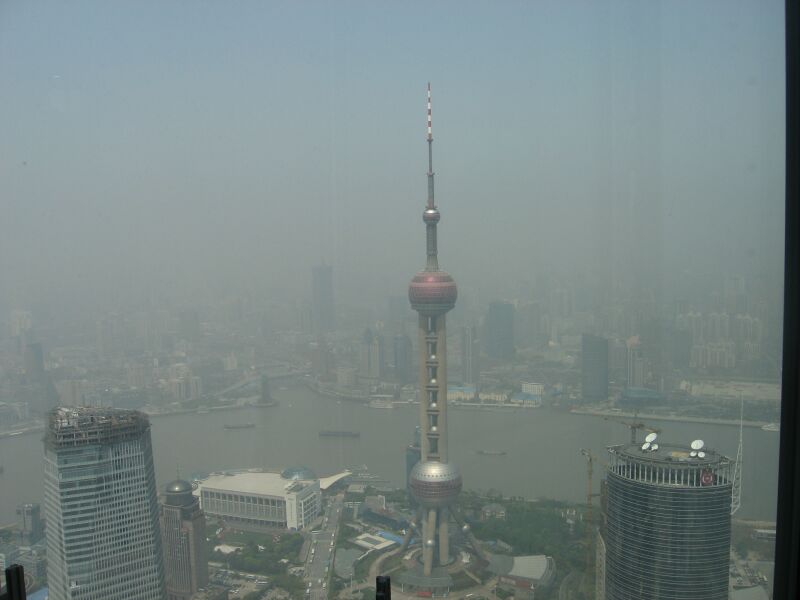

The famous Pearl Tower (a TV broadcasting facility). The degree of haze

shown here seems characteristic of large Chinese cities. Is it an

average day or a bad day? We were not there long enough to make the

judgement. It would be a very bad day here. The haze was pretty

much this thick in Xi'an when we were there.

In the 1930's when Jews were attempting to flee Hitler's Germany, the

only place on earth that offered them sanctuary was the city of Shanghai.

"Just before World War II, the numbers of Jews in Shanghai topped 30,000.

In February 1943, to appease the Germans who wanted the Japanese to

implement the Final Solution in Shanghai, the occupying force of the

Japanese army forced the "stateless Jews" into a "Designated Area" in

Hongkou District (north of the Bund)... Tens of thousands of Jews lived

cheek by jowl in this ghetto, where the local synagogue became the center

of their material and spiritual lives until the end of the war." That

synagogue, Ohel Moshe, is shown above. It is now a museum.

While in Shanghai we took a side trip to nearby Suzhou, where we

enjoyed a short cruise on the Grand Canal that connects Suzhou to

Beijing, visited the classical Chinese garden of a rich man's

house, and walked though a silk factory. The photograph above is of

Suzhou's most famous son, the general and writer Sun Tzu (author of

The Art of War).

China is working very hard to become a modern First World nation. Crazy, evil Mao died in 1976, so China has had little more than 30 years to recover. Now that Mao is gone the Chinese people and government have begun to reassert the underlying vigor and entrepreneurial genius of the Chinese people.

When we visited Lama Temple in Beijing we noticed a sign indicating that Zhou Enlai had saved the temple during the Cultural Revolution. We saw the same notice at another historic site in a different city. When we pointed out to our guide that Zhou was understood in the West as a moderating influence on Mao, she defended Mao by saying that he had provided "a base" on which the modern China could be built - but would go no further. We wonder whether it still is dangerous to criticise Mao.

After 30 years China qualifies in some ways for First World status. People seem relatively wealthy. In the cities there are as many cars as bicycles and scooters. Morning and afternoon traffic jams occur in all the large cities. People from all over China have become tourists, visiting religious and cultural sites in their own country. We were driven on freeways as well-made and with multi-level interchanges as impressive as our own. The skyscrapers in Shanghai are taller and newer than those in Manhattan. The people use cell phones and are connected by the Internet.

English is widely spoken, as in Europe, though not always well. English language signs and descriptions are abundant at sites where Western tourists go. In major museums, for example, all the items on show have descriptive cards in both Chinese and English. This is something we wish more museums in Europe would implement.

There are also ways in which China fails the test of a First World nation. For example, you cannot drink the tap water. Even the Chinese do not drink tap water, which may account for the fact that China is the world's largest producer of beer. True, some folks in our country filter their tap water, but that is to improve the taste or reduce cloudiness - not because the water contains coliform bacteria.

Nevertheless, China seems clean. We have been in a number of third-world counties that are not. Cambodia, for example, is awash in trash - particularly the ever-present plastic bags. China's city streets (those we saw) are clean. The parks are manicured and clean. On the freeways we actually saw people walking along the margins with dustpans and straw brooms sweeping up dust, and others with buckets of soapy water scrubbing the guardrails. Is it a benefit of cheap labor? We know that in America such work would be prohibitively expensive.

And to what degree can it be said that China has a First World political system? Is Western-style democracy a prerequisite for First World status? From Wikipedia: Direct elections occur for village councils in designated rural areas, and for the local People's Congress in all areas. All other levels of the People's Congress up to the National People's Congress, the national legislature, are indirectly elected by the People's Congress of the level immediately below. Executive positions, including the President, the State Council and provincial governors are indirectly elected by the People's Congress of the relevant level. While universal franchise is guaranteed in principle by the Constitution, in practice the Communist Party of China maintains full control of the entire electoral process. In practice, only members of the Communist Party of China, eight allied parties (the "democratic parties"), and sympathetic independent candidates are ever elected in any election beyond the local village level. We add that China regularly imprisons citizens who challenge the government's total hold on power, and offer the example of Liu Xiaobo, who received an 11-year prison sentence for drafting a petition urging political change. Liu died in prison, and here is an open letter from Nicholas Kristoff of the New York Times excoriating the Chinese government for Liu's treatment.

In one irritating way China is reminiscent of Egypt, an undeniable third-world country: almost everywhere the tourist goes he is approached by aggressive trinket-sellers.

The Chinese people are prospering and it shows. The people we met - our guides and drivers, salespeople, chance encounters on the street - were pleasant, open, smiling, and helpful. This is not the reception one gets in some European countries. Unlike the Russians, the Chinese seem not to have been mortally wounded by Marxist philosophy. One of us (Joseph) who was not at all enthusiastic about this trip initially, came away quite pleased with the experience.